![]() Download the full Insight Project article here.

Download the full Insight Project article here.

Negative Emotions are Physical, Mental & Contextual

There are competing theories over how emotions are represented in the brain, how they relate to signals from the body and even over the basic questions of whether there are truly distinct types of emotion. It is unlikely that these questions will be settled any time soon, but there are certain principles that most agree on. These principles offer us important clues about how we might think about emotions and mental distress, how we should measure them and, ultimately, how we might help people to control them. These principles are:

- Emotions have physical as well as mental subjective attributes.

Emotions like fear and anxiety comprise not just thoughts (feelings of impending doom or disaster, the sense of unease, readiness and anticipation) but also physical sensations from limbs, skin, chest and abdomen. Focusing on these physical signals may well prove fruitful.

- No single brain region, physical sensation or subjective state will map directly onto a particular emotion.

Under some circumstances, butterflies in the stomach, accelerated breathing and a racing heart may be unpleasant and frightening, under others, it signals excitement and elation. Circumstances and context, as well as sense of control, dictate just how positive or negative an experience may be. Any attempt to measure and monitor the markers of emotion is going to require a willingness to engage with complex, context-dependent interactions among brain and body signals.

- Emotions are the subjective interpretations of complex physical states.

Emotions depend on our expectations and inferences. Recognising this offers a window of opportunity to the skilled game designer whose metier is the creation of absorbing, compelling situations and narratives. By assuming exquisite control of story and context, the designer has a chance to shift the interpretation of physical experiences and, hence, to help modify emotional responses.

Understanding brain-body relationship is crucial, but games give us the third missing piece – control over the environment

Separating Symptoms from Suffering

Diagnoses like “schizophrenia” can, when applied to an individual, produce fearful and distrustful reactions in others. The ensuing ostracism and stigma can be more distressing to the individual than the experiences which led to the diagnosis: experiences such as voices and persecutory beliefs.

How much of our mental fears, anxieties and illnesses come from the way our symptoms are stigmatised and interpreted? Regardless of symptoms, if you can live a satisfying life without excessive suffering, why should you be labelled mentally ill? Symptoms and suffering can be separated.

There is a huge variability in how people view their experiences. Some embrace the medical view, that they are symptoms of a disturbance or disease: something that requires a remedy. Others, who may have very similar experiences, reject the idea of illness or disorder. Some may choose to embrace these experiences, accepting their reality and valuing their uniqueness.

It is often possible, and indeed, wise to avoid polarised arguments over what is illness and what is not. The important and pressing question concerns the degree to which the experience occasions personal suffering, either directly or indirectly, and, if it does, what may be done to mitigate this. The answer may lie not in seeking to remove or suppress the experience but rather to find ways to alter its effects.

We are not looking for cures for symptoms, but for effective strategies for dealing with fear and distress

Visualising our Mental Health

No one escapes mental suffering. We all experience grief, depression, anxiety, anger, hopelessness, confusion, paranoia and other hallmarks of mental illness at one time or other. It is utterly normal to do so. However, we tend to only pay attention to our mental health when problems are far-advanced, when medical intervention or psychotherapy becomes a requirement by which time successful treatment becomes markedly harder.

Prevention is the best cure, but this requires us to be able to monitor our mental health, which is profoundly difficult because it is complex and abstract. Weakness or pain in a muscle due to over-use is easy to detect and has clear and obvious causes. And we know the best remedy – to go easy on that muscle and remove the stress, which is the source of the problem, at an early stage. But, if we find ourselves feeling low, anxious or poorly-motivated, it is often hard to pinpoint the cause and we may well put it down to some personal failing, resolving to overcome it without really knowing what we are trying to overcome.

We may be irritated at ourselves, trying hard but becoming ever more self-critical as we fail to measure up. We find it difficult to pick up the early signs, to respond appropriately or to recognise further deterioration. And to make matters worse, though most of us are only too willing to complain to a friend or colleague about a torn muscle, and to seek and accept help, the same is not true for mental distress.

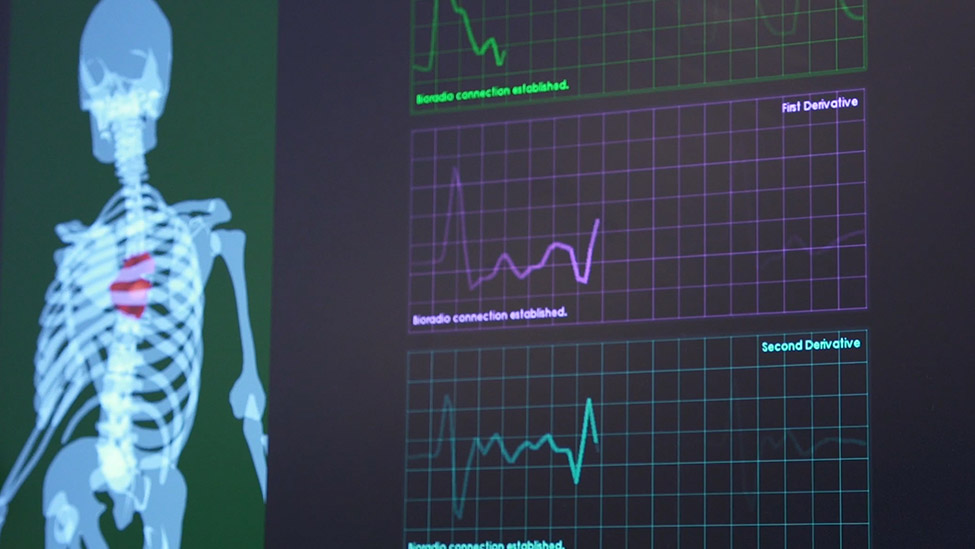

Imagine a technology that can monitor our mental state in real time and represent it so that it can be effortlessly seen or heard. Mental states are complex constellations of experiences and emotions. We need to envisage a technology that could pick up the subtle and basic components of change. These are manifold and may be extremely subtle: shifts in muscle tension, altered cardiac and respiratory patterns, changes in skin and ocular indices of anxiety and tension. If we can develop such technology, and make it easy to apply widely, it’s not a huge leap to imagine this being the first step towards prevention.

An individual could identify triggers and try various strategies, seeing the results of these immediately and thereby finding the one that works for them. In essence, just as the early pain of a muscle tear allows us to take immediate steps to lessen the damage and promote recovery, so a growing subjective access to, and awareness of, the early warning signs for mental ill-health, could provide the impetus and the ability to take the right steps at the earliest stages.

We must manifest our mental state in order to take action and strive for mental wellbeing

Videogames for Mental Wellness

A key principle of meditation involves awareness of the body: the breath, the heart, the muscle tension, as well as awareness of intrusive thoughts. By becoming aware, we can step back and take action to calm and control our body and mind. As healthy and useful as meditation is, it takes a big step to commit to learning such techniques and persist for long enough for it to be useful. It is difficult to do and difficult to know if you are doing it successfully. Many people are put off by these difficulties.

Videogames are designed to engage you for days on end, to teach you new skills, and challenge you in such an absorbing way that mastering those skills becomes a goal and a pleasure. With the right design, using your physiology as an input controller, it should be possible to visualise, guide, and master a game based around your wellbeing.

Videogames engage, train new skills and promote mastery, a toolset that can be applied to mental wellbeing

Overcoming Stigma with Design

Stigma is a monstrous barrier towards seeking support and treatment. A person with a fracture receives sympathy and support and usually has little difficulty in accepting their own needs and the willingness of others to help them.

Conversely, something like depression makes you feel like a failure, a feeling that is kept hidden and sometimes compensated for by avoiding help for fear of becoming a burden. At the same time, personality tests that measure intelligence, emotional IQ, and so forth have no such stigma as they are framed as mental games, not as diagnostic or treatment tools. The enormous success of the Dr Kawashima’s Brain Training videogame is testament to this.

Hellblade, a game where you are asked to play as someone who experience severe psychosis, showed that you can dress complex issues in compelling, emotive and artful ways and present it as a mainstream entertainment experience.

If we want to reach a mainstream audience, the Insight Project should be a compelling, rich and desirable mainstream experience, not a soul-less app of which there is a glut. It should appeal to our desire for entertainment, our curiosity, our need for reward and our thirst for challenge.